West African Migrants Risk Everything, Face Exploitation

In the big picture of human history, we see a world in motion where people are crisscrossing borders as a means of survival and the pursuit of economic opportunity. Migration in any era has always been difficult. But in the current geo-political landscape, tougher border security measures have meant that today’s irregular migrants are increasingly pushed toward more hazardous journeys.

In West Africa, a migrant’s path to Europe often includes a dangerous trek through the Sahara Desert and a precarious voyage in a flimsy boat across the Mediterranean Sea. Over the course of this journey, migrants suffer grave abuses and exploitation by people who profit from their vulnerability. Some are even sold into slavery.

To address the plight of the West African migrant, Catholic Relief Services is working with the Church to protect migrants across five countries, including in Niger, Ghana, Senegal, The Gambia, and Mali. We are also working to address underlying drivers of migration—issues such as skyrocketing youth unemployment rates and intense social pressure to take risks for the benefit of their families back home. It’s not uncommon for a family to go into debt trying to support a migrant’s journey, only to have that journey end in tragedy.

“People are migrating at great peril because they believe they’ve run out of options,” says Petra Suric Jankov, who runs the CRS West Africa migration project. “The pressure and responsibility on migrants is enormous, and it’s what makes our work even harder. We are working with people who are migrating in the name of their entire community. Even if they feel compelled to give up their dangerous journey because of multiple hardships and exploitation endured along the way, time and time again they tell us they would rather risk death than to return home empty-handed.”

Working with West African migrants and their communities, we’ve learned about their plight and about the hopes and dreams many have for the future. Here, we introduce you to four of these West African migrants, each of whom left home with high hopes but encountered treacherous—and ultimately tragic—journeys for a chance at a better life for themselves and the family and friends they left behind.

The Dutiful Daughter

“I feel for my fellow women. They should not embark on this journey. This kind of expedition shatters lives.”

Sara was sold into sex slavery in Algeria by a family friend. She later escaped to Agadez, Niger, where she lives with her infant son, who was born during her captivity.

Photo by Hadjara Laouali Balla/CRS

Sara*, 24, was born in Nigeria into a life of poverty. She never had a chance to attend school, and the family survived by eking out a living doing whatever menial labor they could find.

“We made do with whatever we were able to get. Usually I did arduous jobs … like sweeping, and washing,” Sara says.

Encouraged by a family friend, who advised Sara’s parents that their daughter could earn more money for the family by working abroad, her parents agreed to let Sara migrate. Yet the journey Sara was about to take turned all their hopes into unimaginable nightmares. Traveling through the desert in a small vehicle with three dozen other migrants, Sara was abused and exploited at every point along the way.

“The drivers of the motor cars that took us—they themselves sought out means to take advantage of our bodies. If we refused, they beat us. We spent fifteen days on the road in suffering,” Sara explains.

When she made it to Libya, Sara was sold into slavery by the family friend who her parents had entrusted with her safety.

“She said we should have sex with men and make money to pay her back for bringing us,” Sara explains. “If we refused, she brought other men … When she got what she needed, she left us with the men. They made life hard for us.”

Less than a year into her stay in Libya, Sara became pregnant by one of her captors, who threw her out of his home after finding out. Luckily, a few kind people took pity on her and helped her travel back to Western Africa by way of Agadez in Niger, where she now lives with her infant son Saheed, who was born after she arrived.

She said that traveling as a woman made her especially vulnerable to abuse.

“I feel for my fellow women.They should not embark on this journey,” she says. “I would like to say to them all to stay where God has kept them because this kind of expedition shatters lives.

As for her hopes for her newborn son Saheed, she says, “I want him to be ahead of me. I will love him to be educated.”

The Dreamer

“I was brought up with that orientation, to be a bit of a businessman. It's something very special that I learned from my mom.”

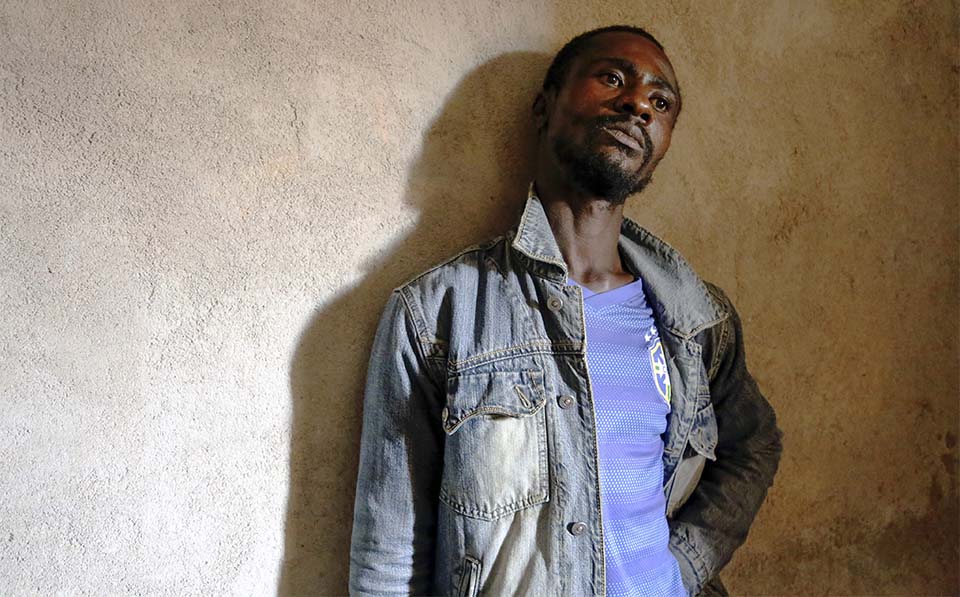

Emanuel Dindul escaped captivity and found his way back to Agadez, Niger, where he works odd jobs to make enough money to survive.

Photo by Hadjara Laouali Balla/CRS

Originally from Nigeria, Emanuel Dindul, 40, knew he was destined for something bigger than the opportunities his village could afford him. Emanuel grew up 1 of 10 children in a house where his strict mother taught him the value of hard work. In fact, he remembers as a boy traveling across villages to hawk bananas on the street.

“I was brought up with that orientation, to be a bit of a businessman,” Emanuel recalls. “It's something very special that I learned from my mom.”

Emanuel stood out in primary and secondary school, earning recognition from teachers as a leader. He went on to study civil engineering, and graduated from a polytechnic school with a diploma in business administration and management. By then, he was married with two children and realities of life in Nigeria set in. As a young man in a country with one of the largest youth populations on Earth—where nearly a quarter of the workforce is unemployed—he found himself jobless after a few failed attempts at business startups.

“I went looking for menial jobs, but I couldn’t find one,” he said. “That is when I decided to leave.”

After speaking with a friend who advised him that he could find work in Libya, Emanuel paid a smuggler to take him through the Sahara Desert. But the trip went sour when Emanuel was robbed by bandits. What’s worse, when he arrived in Libya he was detained by his smugglers in a credit house, which is a place where migrants are kept until they can pay the smugglers.

“We found ourselves brutalized and beaten,” he recalls. “If you made a mistake, they punished you like a slave.”

Emanuel says that while he was in captivity, he witnessed the brutal killing of a teenage migrant who died after being beaten with a broom.

“That really shocked me and made me cry,” he says. “That is when I started regretting that I left. I asked myself, ‘Why didn’t I listen to my wife who told me not to go for this journey?’”

Emanuel eventually escaped captivity and found his way back to the West African country of Niger, where he currently lives in a state of uncertainty. He says he’s afraid that if he goes back to Nigeria, he’ll be ostracized by his community for failing to make something of himself. But despite those fears, he still has high hopes for his future as he continues to work and send money home to his family.

“My hope for myself is that one day I will return back to my country to change it for the better,” Emanuel says. “I want to help young people understand that they can choose to stay where they are—and that they can make it in their country. They don’t have to leave.”

The Baker

“I nearly died in the desert. I was very scared. Thank God, the spirits of my parents were with me. There was this one time I fainted in the desert and people poured some water on me and I woke up.”

Favour nearly died in the desert before arriving in Algeria, where she was ultimately deported.

Photo by Nikki Gamer/CRS

It was purely by chance that 22-year-old Favour* decided she wanted to become a professional baker. Orphaned at the age of 7 when her parents died in a car accident, she was raised by a family friend through her high school years.

“When I finished high school, [my caretaker] wanted me to find a job so that I could support myself. So, I got into contact with a lady in Lagos who helped me with a sales job,” she says.

After selling clothes for a year, Favour got a job at a catering business, where she learned that she was good at baking. In fact, she was so good at it that she soon enrolled in a catering training course, earning a certificate after baking a wedding cake as part of her final exam.

“People were surprised to see the cake I made. I started getting customers,” she recalls.

After earning her certificate, Favour got a job as a baker at a popular restaurant but dreamed of starting her own bakery someday. Those aspirations pushed her to take the advice of an acquaintance and travel to Northern Africa.

“One day, I met a woman who told me, ‘You must travel to make more money so you can open your own bakery shop,’” Favour explains. “That was when I started thinking and making arrangement to leave Nigeria.”

Favour’s journey out of the country didn’t last long. Her plan to travel to Algeria to work for six months ended when she was deported after only two months. What’s worse, when she was deported she was left in the desert to fend for herself.

“I nearly died in the desert. I was very scared. Thank God, the spirits of my parents were with me. There was this one time I fainted in the desert and people poured some water on me and I woke up,” Favour remembers. “Many people died from hypothermia in front of me in the desert because it was very cold at night. I was lucky I carried a big sweater with me when I was leaving Algeria.”

Favour ultimately survived the desert and found her way to Agadez, Niger, where she’s taking a reprieve before making her way back to her home country. Of her future, Favour adds, “Even if I cannot continue with my education, I want to become a professional baker. I hope I will still make it.”

The Striver

“I have a friend that came home from Europe … When he came, he came with big cars, living a fancy life. So he told me, ‘You have to move far. You have to get to Europe. Make up your mind boy. Get up and go out.’"

Jessie Gemes Souliman lost everything after being deported from Algeria. He hasn’t returned to The Gambia for fear that he’ll be ostracized from his community.

Photo by Nikki Gamer/CRS

Jessie Gemes Souliman, 39, a mechanic by trade, had a turbulent childhood in The Gambia marked by political violence.

“I lost two of my brothers, I lost one of my uncles, and also my auntie,” he says of the political violence he endured growing up. As a young man with two children, Jessie Gemes made a decent living as a mechanic working on heavy duty engines, but longed for the perceived riches he saw acquaintances earn abroad.

“I have a friend that came home from Europe … When he came, he came with big cars, living a fancy life,” he remembers. “So he told me, ‘You have to move far. You have to get to Europe. Make up your mind boy. Get up and go out.’"

Jessie Gemes left The Gambia with his wife and children, intending to make it to Europe. However, their plans changed when they arrived in Northern Africa. They decided to stay in Algeria, where Jessie Gemes spent nearly a decade earning a living in his trade.

“It was a very happy time of my life,” he says.

But his luck changed and his family lost everything when they were abruptly deported in the middle of the night by Algerian authorities. In 2017, Algeria began deporting sub-Saharan Africans en masse, stranding them at the borders of Niger or Mali with nowhere to go. Now living in the transit city of Agadez, Niger, Jessie Gemes is contemplating what his next steps might be.

“I have to earn something before going back to The Gambia. I cannot just go back empty-handed,” he says.

“If I had known what would happen to me, I would never have left The Gambia. I would have stayed there and perhaps done something by now.”

* Full names withheld for privacy and security considerations.