Climate Change in Ethiopia: Counting Rains

How do you measure a year? Twelve months? Three hundred and sixty-five days?

In the eastern-most part of Ethiopia, Jemal Bedhaso measures a year not by the number of months or days, but the number of rains.

There are the years of three rains. The years of two rains. The years of one rain. And years like this one.

"We haven't had rain for 1 year," Jemal says, as he squints against the relentless afternoon sun.

"Environmental degradation, deforestation and water supply problems expose most communities to food insecurity," says Belayneh Belete, the program director for a CRS' partner, the Hararghe Catholic Secretariat. "There are many cases of malnutrition as a result." Everyone suffers, she says.

No water, no food, no school

Jemal's worn jelly shoes kick up clouds of white dust as he makes his way over the rocky path that leads from the main road to his home. The path runs among bushes bristling with thorns the size of a child's forearm. Rugged cactuses also grow here.

The sun bears down on his cowboy hat, as he nears home. His weathered face gives way to a big smile when he sees his wife and five of his children outside their mud-brick hut. Even though it is the middle of the day, his youngest children are home. They dropped out of school—as many other students did—because of the lack of water.

"Children don't have the strength to walk to school and had to quit," Jemal explains. "They're not strong enough to go to school. Especially this month, we're starving because there's no water."

Twenty years of changing weather patterns—erratic rainfall, prolonged droughts and flooding—have made it difficult for farmers to know when to plant. Too often, harvests are meager. In communities like Jemal's, where families depend on their livestock for an income, the lack of rain means low prices for their emaciated animals. Children go to bed hungry.

Climate-smart agriculture

The project, called REAAP—Resilience through Enhanced Adaptation, Action-learning and Partnership—will work hand-in-hand with six vulnerable "woredas," or districts, in the eastern state of Oromia. They'll design and put into action plans that decrease the risk of climate-related disaster. The project is funded by the U. S. Agency for International Development.

"We have to employ climate-smart agriculture if we want to effectively tackle extreme hunger and poverty," says Nikaj van Wees, CRS' Chief of Party for the REAAP project. Farmers will learn new technologies and innovative practices that consider not only crop types and soil fertility, but also landscape restoration to address the degraded terrain and climatic conditions.

"What makes REAAP different is that it focuses on people's ability to cope with disasters instead of looking at outside assistance," explains Alemayehn Ayele, one of 50 people who is receiving training on climate mitigation and will share that knowledge with his community. "Before the training, I thought only the government or NGOs can solve communities' problems, but now I understand that we can solve our own problems."

Adapting to climate change

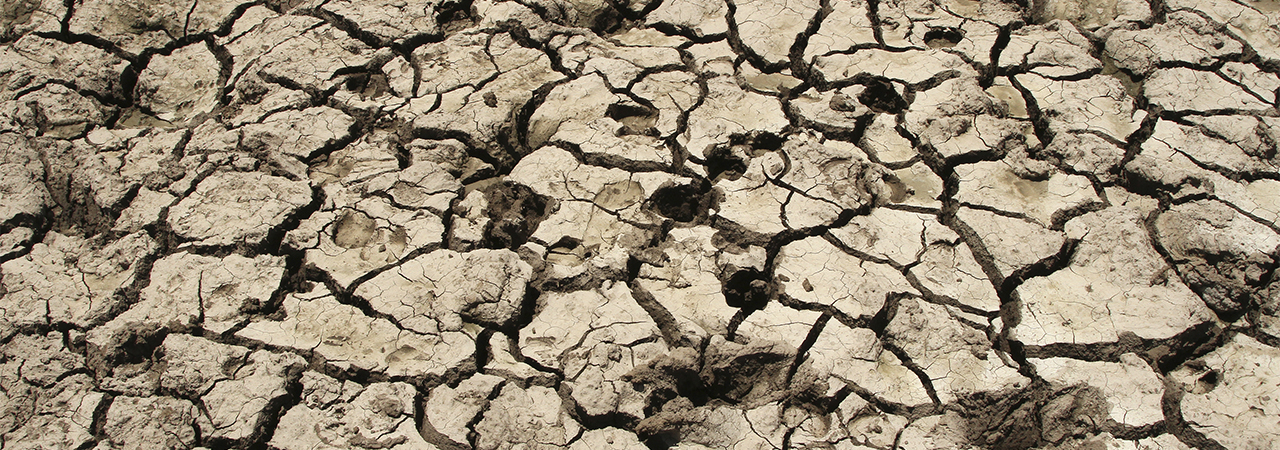

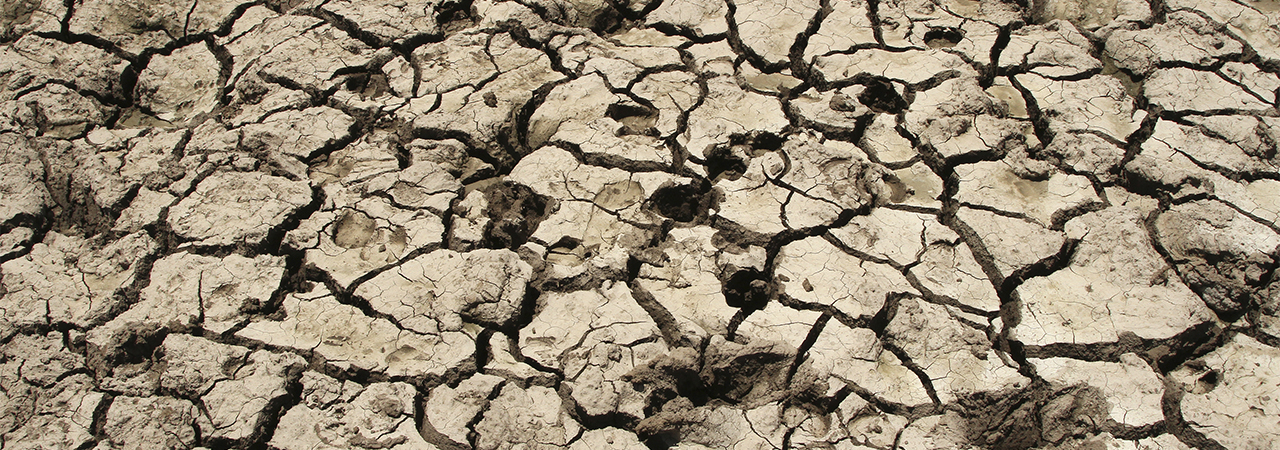

To get to some of the remote towns and villages in Oromia State from its capital, Dire Dawa, you drive on winding roads high in the mountains. You pass over sandy riverbeds that once flowed with water. You see large, dry lakebeds from which the water disappeared 10 to 15 years ago. In many places, the brown, rocky soil of the mountains crumbles away, and ridges made steep by landslides are common. Lush fields and green grass are a rare sight. Only small streams that snake their way through the valley provide desperately needed water for irrigation.

In this region, where Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant Christians, and Muslims live peacefully together, the roads are lined with small storefronts that offer anything from bottled water and chat—a plant commonly used as a stimulant—to used clothes, shoes and household supplies. People and animals alike compete for shade, huddling together under small awnings or in doorways. Although there is food in the market in spite of bad harvests, most people don't earn enough to buy it. Many are forced to migrate to bigger cities in search of work.

In the district of Meiso, families like Jemal's are bearing the brunt of dramatic climate change that has turned their farmland and pasture into a desert. "Twenty years ago, there was more rain," Jemal says. "Today," he says, pointing to a nearby mountain range, "there are no clouds above the mountains where they used to gather. I was a farmer 20 years ago. I even grew coffee here. Our land, 20 years ago, looked like a place in the highlands. It has now changed to a desert. Everything has dried up and totally disappeared."

As he watches his wife grind a handful of corn kernels for the family's dinner—her body pressed against the outside wall of their hut seeking a few inches of shade—he talks about one aspect of adaptation.

"We depend on collecting rain water," he says. "The kind of pond we're digging does not retain the water because we use only soil. We don't have any cement. I know about REAAP and that it will address the effects of climate change. In case REAAP can help us with plastic to reduce the absorption of the water into the soil, we would be very happy. We believe it will help us a lot."